Sarah Lubala is a Congolese-born, South Africa-based writer. Her family fled the Democratic Republic of Congo two decades ago amidst political unrest. They relocated first to South Africa, then the Ivory Coast, before returning to South Africa and settling in Johannesburg.

She has been twice shortlisted for the Gerald Kraak Award, and once for The Brittle Paper Poetry Award, as well as longlisted for the Sol Plaatje EU Poetry Award. She is also the winner of the Castello Di Duino XIV prize. Her work has been published in the Mail & Guardian, The Daily Vox, Brittle Paper, Apogee Journal, Entropy, and elsewhere.

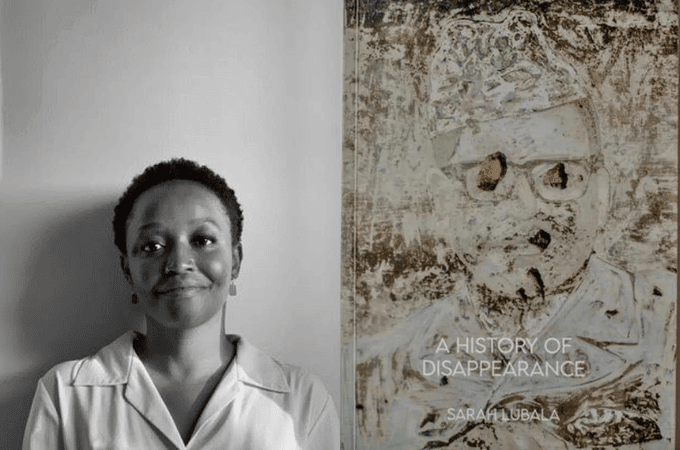

Her debut collection published in 2022, A History of Disappearance, contains 37 poems and photographs by Julien Harneis, Bill Wegener, and others. Some of the themes addressed in the anthology include forced migration, displacement, xenophobia, gender, sexual violence, mental illness, memory, and remembering.

Has writing always been part of yourself?

Words have always been a part of me. I started writing poems and short stories when I was 9 to try to make sense of my experiences. I grew up in a house where violence was a real and felt presence. It was hard to feel any sense of safety, at home and in myself. Writing helped me carve a space for myself.

What inspires you to write, who are your inspirational figures both in real life and in literature?

I think writing is a lesson in paying attention, and I’m curious about most things. I’m inspired by most things, particularly if they’re considered quotidian. I’m interested in the luminosity of ordinary life. The hadedas screeching in my back yard, my mother’s singing voice, my relationships with my loves, and on and on, it all inspires me to write.

I’m deeply inspired by the women in my life, and they often feature in my writing. My great grandmother, my grandmother and my mother have lived remarkable lives – lives filled with a great deal of pain. Their resilience and triumphs continue to move me.

Your family fled the DR Congo twenty years ago and you have dedicated several poems to what it means and feels to be a refugee. Have you got any memories of this event?

My family left the DRC when I was 3 years old, so I only have snatches of memories. But memory doesn’t just live in our minds, our bodies remember too. I suffer from chronic pain as a result of early traumas, even those I don’t wholly remember, even those of earlier generations, because their histories are passed down to us. Intergenerational trauma is, in some sense, the burden of unresolved histories.

Having experienced migration yourself, how does it feel to see that migrating is still a necessity for so many people (due to civil wars, climate crisis, famine…)?

I’m devastated by it. Forced migration is a lesson in loss. You learn that all things are temporary, anything can be taken from you, even a country. I know that loss intimately, and my heart breaks for those who know that loss too.

Our project focuses on African women’s poetry. How is femininity present in your work?

Although I believe that poetry is for everyone, I write for women. Those I know and those I don’t. All my poems are infused with their stories. I think of my writing as joining a chorus of female poets.

And do you think there are specific features to African poetry? And to female African poetry in particolar?

I don’t know. I think African poetry is too broad a thing to distill down to any specific features. Perhaps the thing we have in common is that we write about the reality of our lived experiences.

Your first collection of poems, “A History of Disappearance” has been published in 2022. What is it that has disappeared but it’s still worth telling?

A History of Disappearance traces my experience as a Congolese-born immigrant. My family fled the Democratic Republic of Congo two decades ago amidst political unrest as militant factions tried to overthrow the dictator Mobutu Sese Seko.

What are you currently working on? Any future projects in sight?

I’m currently working on a collection of creative non-fiction essays centred around the themes of endings.

Interview by Gaia Resta

Link to the interview in Italian

****

Read Portrait of a Girl at the Border Wall

Read Dispatch from Ward C, from One Global Voice – project on mental health promoted by Voci Globali