Abigail George is a South-African feminist, poet and writer based in Port Elizabeth. Born in 1979, she is a prolific writer: she has written a novella, several books of poetry and collections of short stories. She is a Pushcart Prize nominee and the recipient of two South African National Arts Council Writing Grants and of one from the Centre for the Book and the Eastern Cape Provincial Arts and Culture Council.

Describing her origins, her sense of identity and her writing, she told us: “I am told George is a well known surname on the island but thing is those George’s look is European. The texture of my hair gives me away. I could never pass for a European and neither do I pass for an African. It is as if the blood that is pumping through my veins is pretty much like the reality I have become so used to living in. Divided, crooked, disjointed. I mean what, who do I represent? The African continent or a much more European outlook on life with an American sensibility?”

When and how did poetry appear in your life?

When I was very young. I was four and then it kept on building and building up inside of me as if I was a spinning top, child’s play, or as if I was a cog in a well oiled machine. Poetry was a feature in my life before the end of the era of apartheid in my country, a still pretty much racially divided country. You still turn on the news today and you see brutality against the weak, the helpless, those that have limited resources to fight back. You still see the semantics of years and years and years of a political discourse running through the narrative of the context of the psychological framework of every South African and African man, woman and child.

As a child I lived virtually in a world of my own creation and imagination. I had a journal as a child in primary school. I had mild depression at the time. Already at that young age of eight, I was sending my work away to the local newspaper. That is how poetry appeared in my life. Through tragic events. The death of my beloved mute grandfather; I couldn’t get a handle on loving relationships after his death so I withdrew from the world into my writing.

You are a very prolific writer: you have written several essays, novels and poetry collections. You seem to be gifted with an overwhelming creativity that finds expression in multiple dimensions. Where does this unstoppable drive to write come from?

Pain. Traumas. Nervous breakdowns. Being institutionalised for depression for six months at a state hospital in Johannesburg and spending hours doing occupational therapy to calm the noise inside my head. The voice that kept on telling me that I was never going to be good enough, nobody was ever going to love me. So I have all these multiple dimensions in me, these layers filled with from one paradigm to another, one persona, one mask, one costume.

I have struggled with mental strain and exhaustion and insomnia all my life. Yes, bipolar and mental illness, the suffering and sorrow of others has also played a role in my life and devotion to poetry. But know this. I have always, always, always seen poetry as a blessing in the natural sense and it has existed to me like the law of gravity, the laws of thermodynamics, the rapid cycling of mania and hypomania and ether, air, fire and water.

It saved my life repeatedly. Its flame would burn out and then magically I would be restored to life again and that supernatural blessing that came from beyond the grave to the infinite universe would be lit inside of me again where it was always winter. Aren’t poets always considered to be interlopers, especially contemporary female poets no matter what race, faith, cultural background, nation, tribe, quest they are on or which country they come from?

Your poems seem to recreate the experience of dreaming: the reader goes through ever-transforming landscapes, states of mind, atmospheres, then meets relatives, friends and famous people. Words echo through the air or in the head, memories materialize. Do you recognize your work in this description? Can you describe us your writing process?

I work. I work very, very hard to create those vivid landscapes of escape, a time capsule filled with a child’s treasures. In all my writing whether it be an essay, op-ed, a short story – when it comes down to it with the short story – I mostly emulate both Jean Rhys and F. Scott Fitzgerald. In the world of my novellas, I am reaching out to the glorious figurehead of the younger version of Hemingway driving ambulances in the war before he was wounded, before Paris, before Spain, before the Hemingway that met Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. The one key and notable figure that I most relate is not female, not even close to being a poet, it is the philosopher Nietzsche.

You put the former part of your question out there as if the writer itself was a being detached to a much more subtle realm and I really like the words you chose. I have lost count of the times when I would ask someone to come and save me. So I write and when I write it is as if I am in a delirious state asking me, myself and I to come again and again repeatedly to save the drowning girl from the deep end of the swimming pool, or to stop her from diving into the shallows and lifting her lifeless body from the grave that is the sea.

Your poems are often entitled to other writers, poets, artists. The very texts of the poems are often inhabited by literary characters or artists from literature or cinema, in a way that creates a complex network of intertextual and intercultural references. What does intertwining your art with others’ mean for you?

Freedom. Freedom from the mindset, attitude of slavery. Complete, total and absolute liberation.

In some of your poems you describe emotions related to depression. You have also recently written a collection of short stories on notable women in history who committed suicide because of their mental health issues. Why do you feel the urge to find an artistic expression for these feelings?

I love truth too much. I find so much beauty in it even though its boundaries are like seawall. Ready to spit you of the ocean or swallow you and your very authentic boat whole. In my own home and family on both sides there has been a history of the blueprint of madness versus the existential map of pure genius, alcoholism and drug addiction. It was tough to process this and the stigma of having a father who was mentally ill and who had been at the same hospital as South African poetess Ingrid Jonker – who had been lovers with André Brink, famed writer, scholar and academic. The notorious Valkenburg Psychiatric Hospital. It informed a lot of my writing in later years, my two blogs and my poetry.

Your being such a prolific writer may suggest that writing is a full time job for you. Is this your case or is writing a secondary activity?

Well now that my computer is in for repairs I have time for a normal routine. I do household chores, I cook a little, I spend hours and hours of quality time with my beloved parents. I try and not to think of regret but it does come up from time to time. So for now this past year of quarantine and lockdown and the worldwide aftermath of the second wave of Covid, writing has become a secondary activity.

According to you, is it possible to talk of African women’s poetry? If yes, can you identify the elements that characterize an African women’s art of poetry?

I do [think that it’s possible to talk of African women’s poetry] and I don’t read African female, women’s poetry as often as I should and it is not as if this is an unwritten law with me, I just never got given the opportunity. Where are they? In America they receive more publicity especially if they have received a prestigious college or university education. I stay far away as I can from publicity in my home country. I mean, this is where my origins are but I feel more connected to countries outside the borders of Africa.

It truly is a rainbow nation. I do know female poets, but I do not know their work on an intimate level. But I am filled with a deep awe, respect and admiration for women poets on the African continent. They are continuing to make strides in leaps and bounds.

What is your latest work? And would you like to share with us your plans for the future?

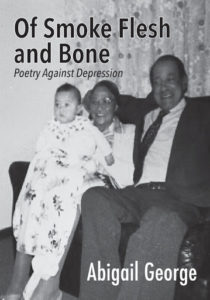

I have so much work coming out all the time. Praxis [a magazine on art and literature] brought out a free chapbook to download entitled The Anatomy of Melancholy, then there is a collection of semi-autobiographical short stories based on notable female figures in the history of literature that changed the writing world and turned the revolution of women upon a literary world that had always been dominated by a patriarchal system. My very, very latest is something that is really close to my heart. It has a picture of my paternal grandparents on the cover.

All my works deal with the topic of just how territorial and unforgiving and intolerant people are of mental illness. The stigma is still out there and so I hope I can impact the world one installment at a time of the chapters of my life. The oppression, the emancipation but also the liberation.

Interview by Gaia Resta

Link to the interview in Italian

****

Read Please help revise the jalapeños and Theodore Roethke, included in One Global Voice – a project on mental health promoted by Voci Globali

Read Jean Rhys

Read Nusayba Alareer

Please want to publish my poem

Great