At just 24 years old, one might not expect such acute awareness, such tangible sensitivity, capable of recounting raw and painful realities with clear, transparent, effective words. But we are in Liberia, and she belongs to a generation born while the second civil war was still raging, enduring its effects in the difficult civil and social reconstruction that followed. A generation that has seen the consequences in mutilated bodies, broken minds, and stories full of horror. We must remember that the country endured an almost uninterrupted period of internal conflict (first civil war 1989-1997, second civil war 1999-2003). A conflict that shocked the entire world due to the forced recruitment of children.

Today’s social issues are no less tragic than the phenomenon of child soldiers. They simply lack international attention. But it is thanks to people like Aria Deemie – a young journalist and poet born in 2001 – that the most vulnerable are not forgotten, and their stories become news, but also poetry.

Human trafficking, environmental destruction, and commitment to fact-checking are the main themes she covers as a journalist. Then there is poetry, which gives space to empathy and nourishes it. And so her verses too recount things that are hard to hear, simply with a different language and emotional involvement.

We interviewed her at a particularly happy moment in her poetic career. Listening to her instills trust and hope in the youth of this country.

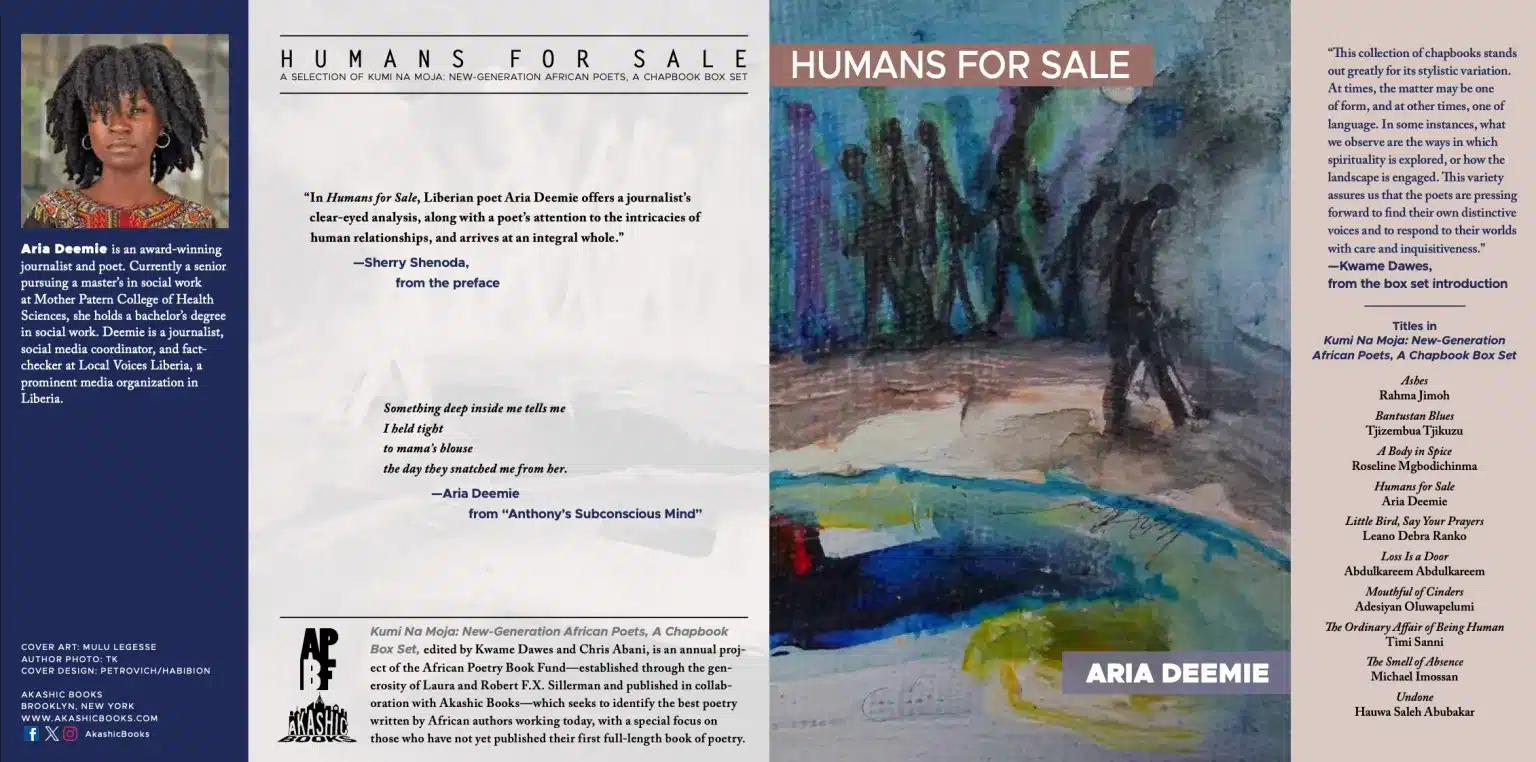

Aria Deemie, you are the first Liberian woman to be featured in the New-Generation African Poets Chapbook Box. It is an annual, limited-edition collection of chapbooks featuring emerging African poets, curated by Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani. What did you think and how did you feel when they told you?

I always smile when I’m asked this question, because I remember that moment as if it were yesterday. When the acceptance email arrived, my first reaction was disbelief, followed by an overwhelming sense of gratitude. I was at a busy school function when I saw the notification. Instinctively, I struck my open palm with my fist, a gesture of shocked joy. People around me stared, confused about what had just happened.

Being selected felt personal, and also historical. I wasn’t just entering a prestigious literary space; I was entering it as a Liberian woman, carrying with me the weight of a country whose stories are often underrepresented or misunderstood. I reflected on how my writing journey began quietly, almost invisibly, with poems written for advocacy, shared online, and at times plagiarized or used without credit. To move from that space into one of global literary recognition, under the mentorship and editorial guidance of Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani, was emotional.

I felt pride, yes, but also responsibility. Responsibility to Liberian writers, to survivors whose stories inspired my work, and to younger poets watching from home who might now believe that this door is open to them too. That moment was electric, filled with renewed hope and faith. Like, God did this.

Your chapbook is Humans for Sale a title that’s powerful enough. Tell us about it. What’s its message, is there a common thread that links the poems and what you want audiences to take away from it?

Humans for Sale is rooted in Liberia’s lived realities of human trafficking, particularly how poverty, inequality, and lack of information turn human beings into commodities. The title is deliberately confrontational because trafficking itself is brutal and unapologetic.

My background as a fact-checker and my training in social work at both undergraduate and graduate levels shaped this work greatly. I have seen how systems are influenced, how ignorance becomes normalized, and how silence allows harm to continue. There is a saying that the day you stop learning is the day you start dying in thought and ideas, and I have lived by public sensitization because I have witnessed how awareness can save lives, restore morals, and open minds trapped in fear.

At its core, the common thread across the poems is resilience. While the collection exposes harsh truths of children sent away under false promises, passports seized, bodies exploited it also centers survival. Although the characters in the poems are not specific individuals, they are composites of real experiences I encountered through my journalism. They resist erasure. They endure.

What I want audiences to take away is awareness without pity. Trafficking does not always look like kidnapping. Often, it begins with hope of parents believing they are securing a better future for their children, young people trusting intermediaries, communities normalized into silence. The book asks readers to confront complicity, policy failure, and moral responsibility, both locally and globally.

Do you think your work, as a journalist as well as a poet, can help change things? If this happened, can you give us an example?

Yes, I do, and I’ve seen it happen.

Journalism creates evidence while poetry creates empathy. I often say that poetry is a kind of mystery, it allows me to speak to people’s consciences without pointing a finger. You know what needs to be heard and what needs to be done, without being instructed. Art is power, power in color, in abstraction, in multiple interpretations and perceptions. That is why poetry stands out for me.

As a journalist, I am not an advocate, I present facts, context, and accountability. But as a poet, I carry a wand. I can bring truth to life without naming it directly. When I reported on trafficking, the facts helped inform policy conversations. But poetry allowed people to feel what statistics cannot convey. I’ve seen readers engage more deeply with the issue after encountering it through verse.

In one case, excerpts from investigative reports were later used as found poems in Humans for Sale. That blending of journalism and poetry sparked conversations among readers who might never approach policy-driven reporting.

Change doesn’t always come through laws or reforms. Sometimes it starts with awareness, with conversation, with unease. My journalism and my poetry exist to interrupt silence.

Are there things that poetry can tell better than a reportage?

Absolutely. Poetry can hold contradiction without resolving it. It can communicate trauma without flattening it into soundbites. Where reportage has to be precise and verifiable, poetry is allowed to linger in emotional truth.

Poetry creates space where grief, rage, and hope can coexist. It can say what survivors cannot always articulate directly. It does not rush to conclusions, it sits with the wound.

And the truth is, before I ever knew what journalism was, I was already a poet, a stubborn voice searching for change through art, insisting on language as a way to remake the world.

You’re also a journalist and focus on social issues. Can you share some of the investigations you are more proud of?

It’s hard to pick just one investigation because I’m proud of all the stories I’ve worked on. I aim to dig deep, bring issues to light, and put people’s voices at the center of policies that affect them. For example, my investigation into the Green Climate Fund Climate Information System weather project exposed how a ten-million-dollar early warning system meant to protect communities was stalled. I’ve also reported on extreme heat and the hidden human toll of what’s often called deforestation, capturing voices like 89 year old Charles McGill’s, who says, ‘We don’t want to keep cutting trees, but we have no choice.’

My work on water contamination at the Whein Town landfill showed that from the start, the site was likely to pollute the community’s water. Residents now rely on contaminated sources, facing snakes, rodents, and disease, while government-constructed reservoirs no longer function. I’ve also reported on trafficking in persons (TIPs) when Liberia risked being downgraded to Tier 3 by the U.S. government. Our coverage, combined with government action, helped prevent the ban in 2019. While I’m proud of that outcome, the realities remain; survivors still live with trauma and consequences. Across all my work, my goal consistentently is to reveal the realities people face and ensure their voices inform decisions.

Do you think journalism in general can be a source of justice and empowerment? And what about poetry?

Yes. Journalism empowers by informing citizens and holding power accountable. It provides documentation, visibility, and pressure, creating a platform for change. Poetry, on the other hand, empowers in a different way. It restores dignity, allowing people to see themselves reflected, humanized, and remembered.

Justice needs both the facts to demand change and stories to sustain it. A journalistic piece can raise awareness with evidence and context, while poetry can demand justice with an immediacy and emotional truth that facts alone often cannot.

A good portion of your journalistic work is dedicated to climate, environment, and science. What are the most dramatic situations in this regard in Liberia?

Liberia is facing escalating climate threats from extreme heat, unpredictable rainfall, flooding, coastal erosion, deforestation, to the lingering effects of weak waste management and stalled systems from the previous administration. The most dramatic issue, in my view, is how climate change magnifies inequality.

Farmers often lack access to weather data, making their livelihoods more vulnerable. Urban communities experience heat stress without adequate green spaces, and informal workers like market women, landfill workers, face daily exposure to environmental hazards with little or no protection. While reports suggest the current administration is attempting to address some of these challenges, oversight and awareness are still lacking, and the Disaster Management Agency says it is underfunded.

You were born and raised in Liberia and are part of a generation that inherited the disturbing stories of war and the heavy silence that follows peace. How much does this silence weigh on you, and where is it broken?

I was born in 2001, but I grew up inside the war’s aftermath. I inherited it through my parents and grandparents, through stories that were never abstract, never distant.

I come from the Mano ethnic group. My understanding of the war began with my mother’s stories. She often tells me how, as a young girl, she once sat in front of the television and listened to a sitting president speak openly about eliminating the Mano and Gio people from Nimba County. That moment marked the beginning of terror for many families.

The day my maternal family fled their home in Monrovia for Nimba, they left under cover on the last National Transit Authoritu Bus, with a driver who hailed from Nimba but was fluent in the Krahn dialect. Armed men stormed the house after they had already escaped, acting on information given by a neighbor, a Krahn man. When my family was not found, he was killed in their place. Very quickly, however, the war stopped recognizing tribe. The other tribes who fled the yard later unvieled this news to them. The Krahn people, too, were later massively targeted and killed. What began with ethnic persecution evolved into a war that consumed everyone. No identity offered protection. The war no longer knew tribe.

My grandfather was a reverend. On the day he had fled with the family in the bus, he was also advised to seek refuge at the Lutheran church, but his instinct told him to flee Nimba instead. Later, it became clear that those who sought shelter there were massacred. Had he stayed, my family would also not have survived.

The war reshaped everything. My family moved from a stable, middle-income life into village survival, and eventually into exile. I have seen the scars across my tribe, and beyond it. My father, also Mano, carries his own memories. And as I grew older, I trained my eyes to look beyond ethnicity, to see how an entire nation was torn apart, fragment by fragment.

I grew up listening to stories of flight, torture, and loss. My mother often speaks about her father, once a respected man with a good job, walking from Nimba to Côte d’Ivoire during the war, carrying farm produce on foot to keep her siblings and her in exile for school alive, then walking back again. She believes those sacrifices broke his health. We lost him later. The war did not end when the guns fell silent.

I was born in 2001, during the final violent phase of Liberia’s civil war, which lasted from 1989 to 2003. My mother was back in Nimba with my siblings and me – toddlers, one child with a casted leg, another still a baby. She moved us to exile however she could: by foot, by bus, wherever survival allowed. Hiding places were never truly hidden.

I don’t remember the rockets or the gunfire, but I remember my mother’s voice saying, “You could have died during the war.” I also remember hope. When Charles Taylor was arrested, people said there was a rainbow around the sun. When Ellen Johnson Sirleaf was elected, my parents dressed in white T-shirts, blue jeans, and white caps, and joined the celebrations. That felt like sunlight after a long storm.

Years later, after the war, my family returned to Monrovia. They refurbished that same house they once fled in fear, and my grandmother still lives there today. That home stands as quiet proof of return, resilience, and continuity after displacement.

Today, the silence lives in grief, in stigma, and in the dangerous idea that forgetting equals healing. What has been lived can always be relived in memory, in the subconscious, in inherited trauma.

The silence also lives in unresolved accountability. War crimes were sentimentalized. One person’s perpetrator became another person’s hero. Guns, once framed as protection, turned into instruments of massacre, rape, brutality, and the violation of women and children. I listen to survivors tell their stories often, and I know: the wounds are still open.

Sometimes I wish we could go back to undo the power imbalances, the foreign influences never accounted for, the corruption that still watches the country’s gold while people remain wounded. But as we say here: no more to fourteen years of suffering. We cannot go back.

Young people are the backbone of Africa yet remain excluded from politics and decision-making. Why?

When I was a child, there was a familiar cookie jar in many African homes. You would reach for it expecting biscuits, only to find needles and thread inside. What looked like something meant to be shared was actually a tool for control.

That is how politics often works for young people in Africa.

Young people are excluded because systems fear disruption. At the same time, youth are made vulnerable to manipulation by dictators and corrupt politicians, mostly from the older generation who know how to exploit desperation. When those in power have already consumed all the cookies in the jar, they replace them with needles, ready to prick anyone who dares to reach in again.

This is why I have always been uncomfortable with partisan politics. I have seen how it robs people of rational thinking when power benefits them. In government, wrongs are ignored; only in opposition are they suddenly visible. As long as young people are offered crumbs, small payments, favors, or promises, policies, age equity, and genuine advocacy are sidelined.

Power remains concentrated because access to it is tied to age, wealth, and patronage, systems inherited from traditional structures where authority was reserved for chiefs and elders. Age has always been associated with wisdom, and in many ways it still is. But wisdom should not be mistaken for monopoly. Today, youth are often consulted symbolically but rarely trusted with real authority.

And yet, young people are already leading in activism, art, climate action, journalism, and community organizing. Some have refused to stand the status quo and rise above transactional politics. They understand that inclusion cannot remain rhetorical. It must translate into real seats at the table, real decision-making power, and real accountability. Africa’s future cannot be built on crumbs and needles. It must be built on trust, equity, and shared power.

Among the many atrocities of that period were gender-based violence and rape. Justice has never truly been done… Even today, GBV remains widespread. What’s the situation in Liberia, and do you address it in your writing?

In Liberia, GBV is a major, unresolved crisis. Legal frameworks exist, but enforcement is weak, convictions are rare, and stigma silences survivors. Seeking justice often exposes victims to blame, disbelief, or retraumatization. Violence persists not only because of individual actions, but because of systemic failure.

Although Humans for Sale focuses on human trafficking, GBV is deeply embedded in the story, particularly in how women and girls are exploited, silenced, and dispossessed. Trafficking does not exist in isolation; it is sustained by the same inequalities, power imbalances, and cultural norms that enable sexual and gender-based violence.

Beyond this work, my writing consistently confronts GBV. I have written several poems addressing sexual violence and women’s autonomy, including A Female Creed and A Country Where Culture Overrides Sexual Violence. In 2019, my work was part of the “Say Enough” Cypher, an Oxfam Liberia initiative exposing the root causes of GBV, challenging victim-blaming, and demanding accountability. My goal has always been to raise awareness.

In addition to writing, I have joined advocacy initiatives using art, storytelling, and community engagement to push back against normalized violence and insist that the lives and bodies of women and girls matter. Because, until justice in Liberia becomes consistent, survivor-centered, and enforced, addressing GBV will remain both a political and cultural struggle.

Which women have been points of reference in your life—personal, public, or historical?

My mother, first and foremost. She has been my earliest and most enduring point of reference. She lives with an unshaken faith through Christ Jesus, one rooted in accountability, discipline, and compassion. Through her example, I learned resilience long before I learned language for it.

Robtel Pailey is another powerful influence. Witnessing her serve as Liberia’s 177th Orator was a defining moment for me. When she took that stand and spoke without fear or favor, speaking truth to power, with power, and straight to the soul, I felt chills. Since then, I’ve followed her work closely. She represents intellectual courage and unapologetic clarity.

I am also deeply rooted in Black history and in the work of contemporary Black writers, and among them, Maya Angelou remains a constant guide. Her words have long resonated with my own philosophy of life and art: “My mission in life is not merely to survive, but to thrive; and to do so with some passion, some compassion, some humor, and some style.”

That mission mirrors how I strive to live, write, and move through the world.

*****

Interview by Antonella Sinopoli

Link to the Italian translation

Read Bessie’s Lament

Read Mrs Gray

Read I Am The Thing That Never Stops Trying

Read Know Your Worth